Features, Research

Puppy Kindergarten

The Puppy Kindergarten

On a quiet corner of Duke’s campus, five students are waiting for class. They relax on the grass, eating snacks and kicking each other playfully. By the time they finish their studies, they will be part of an elite corps of graduates who are not only specialized in a challenging career, but will change someone’s life for the better. The journey of these five students is long and arduous, and it begins at Duke. But for now, they soak up the Fall sun and when someone brings a ball, they all get up to play until it is time for class.

Duke Canine Cognition Center’s Puppy Kindergarten Fall 2021 class photo, from left: Ethel, Gilda, Dunn, Gloria and Fearless.

The Duke Puppy Kindergarten is a five-year project funded by the National Institute of Health. The goal of the project is to increase the supply of service dogs by studying the cognitive development of puppies. Brian Hare, professor of evolutionary anthropology and psychology and neuroscience leads the project , and his wife, Vanessa Woods, manages the volunteer program and the care of the puppies.

Vanessa Woods, Director of the Duke Puppy Kindergarten

The puppies come from Canine Companions, the largest service dog organization in the U.S. Canine Companions' dogs help people with a range of challenges, including mobility issues, hearing loss, PTSD and autism. Depending on who the dogs are helping, they can light up a dark room, alert their owner that someone is at the door, pull a wheelchair, help with the laundry, or sleep next to someone who is restless during the night.

There are millions of people with disabilities who could benefit from a service dog, but the number of service dogs falls significantly short of meeting the need. The work of the program is helping to address this need.

We’re funded, really, because there is a problem in society where dogs are amazing at helping us solve problems, but there’s not enough of them. So that’s really at its core what it’s about, it’s about understanding how dogs develop so we can help more people in need.

- Brian Hare, PhD, associate professor of Evolutionary Anthropology and Center for Cognitive Neuroscience

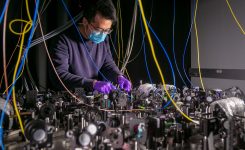

The puppies in the class of Fall ’21 are not only learning the skills appropriate for their age, they are taking part in groundbreaking research on canine brain development. When the puppies are eight weeks old, they play a set of cognitive games that reveal how they think, solve problems, and navigate their world. The puppies play this set of games every two weeks, during their final rapid period of brain development, until they are 20 weeks old.

Doctoral students Hannah Salomons and Morgan Ferrans conduct behavioral testing on sisters Gilda and Gloria in the Duke Puppy Kindergarten. Ferrans and Salomons are also testing the puppies’ heart rates with a monitor, as well as their adrenaline through saliva testing.

The results of these games describe when certain cognitive skills come online, which in turn provides clues to essential questions related to development of effective service dogs. For instance, when do puppies develop self-control? At what age do they start to use human gestures to solve problems?

In adding to our knowledge of dog cognition, the games also help predict service dog success or identify specific cognitive strengths for each dog. For example, in a working memory game, a human handler shows the dog that she’s hiding a treat under one of two bowls, then waits for 20 seconds before letting the puppy choose which bowl.

Handlers play a series of cognitive games with the puppies to measure their particular cognitive skills in different areas: self-control, communication, memory, retrieval, odor detection, and training. Above, the puppy class of Fall 2021 is scored on how well they did in each area.

In this game, Gilda scores 100%. Every trial, from 8 – 20 weeks, she remembers perfectly which bowl the treat is in. Dunn, however, makes a few mistakes. Ethel cannot even play the game until she is 12 weeks old – before that, she falls asleep during the 20 second delay.

Another game showcases the puppy’s self-control ability. In this game, the handler places a treat inside a clear cylinder. The puppies have to stop themselves from bumping into the cylinder and instead go around to one of the open ends to get the treat.

Gilda demonstrates the robot lion test.

The puppies also play games that test temperament. While cognition is the way your brain receives, processes, and uses information to solve problems, temperament is how you behave in situations that are emotionally charged or unfamiliar. Cognition and temperament are usually treated as two different processes, but they interact in complex ways in the brain. For example, a dog can’t solve a problem if she is too afraid to try.

One of the games is how the puppies respond to a robot lion. The lion senses movement, and when a puppy moves toward it, the lion roars, and occasionally dances. Gilda and Gloria are twins, but they have two different temperaments. Gilda is curious and playful with the lion, while Gloria is wary and unsure.

At the end of the day, first-year student Juliana Alfonso-DeSouza brought Fearless to her East Campus dorm room 1-3 times per week throughout the Fall semester to help care for and socialize him. “This experience has helped me discover a new interest of mine, cognitive neuroscience, and has helped me navigate the transition of adjusting to life as a Duke student—after all, there’s nothing better than puppy snuggles after a long day,” said Alfonso-DeSouza, a Rubenstein scholar.

Another important goal of the project is to see how different rearing styles affect a puppy’s chance of success. At the Duke Puppy Kindergarten, the puppies are perhaps more socialized than other dogs. Instead of being raised by a single person or family, Dunn, Ethel, Fearless, Gilda and Gloria have many parents, and all of them are Duke undergraduates. The puppies have a team of night parents and spend a few nights a week in different dorms. They have more than a hundred parents who care for them during the day.

The puppies go all over campus, encountering a diverse range of people and situations. They go to the hospital and visit with nurses and doctors to improve staff burnout and to the Student Wellness Center to help students decompress in the meditation garden. And every weekday, at 2 p.m., they welcome visitors to the puppy park behind the Biological Sciences Building.

The Duke Women's basketball team welcomes its first male teammate, Dunn

Left: The puppies chew on ice cubes as students enjoy their company during an afternoon visiting hour session at DPK. Center: Decompressing with "Puppies at the Student Wellness Center," a Moments of Mindfulness program hosted by DuWell. Right: A student volunteer trains Fearless to walk on a leash with a continuous supply of treats.

student volunteers from Spring 2018 to Fall 2021

Finally, the day comes when the puppies graduate from the kindergarten. They have learned to sit politely when making a request. They can shake your hand, and lie down quietly at your feet. They know where and when to go to the bathroom. They all sleep soundly through the night. They know how to play nicely together, and how to spend time alone.

Most importantly, the students and researchers have learned from them about their brain development and how we might help graduate more dogs into service jobs.

Too soon, Dunn takes a road trip to Nashville to meet his new raiser. Ethel, Gloria, and Fearless all fly to Orlando, Florida, to meet theirs. But the youngest puppy, Gilda, is staying at Duke. She is the 33rd puppy of the Duke Puppy Kindergarten, and her raiser is Morgan Ferrans, a graduate student studying the cognitive development of puppies. Ferrans will mentor Gilda on her journey to become a service dog, and in return, Gilda will teach Ferrans in even finer insights into the mind of a puppy.

When the new class of puppies arrives in Spring ’22, Gilda will be there to meet them.

Puppy alumnus Ashton opens the door for his companion, Nancy Liles, in Tennessee

Doctoral student Morgan Ferrans is caring and training Fall 2021 alum Gilda for the next year on her path to becoming a service dog. Here, Morgan walks Gilda through downtown Durham to Central Park.

Produced by Duke Digital & Brand Strategy

Story by Vanessa Woods

Photo and Video by Jared Lazarus

Additional video by Veronique Koch, Selena Castillo and Jacob Whatley

Design by Caroline Pate